The software delivery process and technology, popularly known as CICD (Continuous Integration + Continuous Delivery), is a structure supporting your software (development) lifecycle.

CICD is the one of most overloaded terms in modern software development, my theory is that at the moment something gets into a job description as a skill, it takes life of its own and is hard to determine the generally applicable definition. In this article, and ones I wrote before, I am referring to CICD as an SDLC supporting structure, as a process and set of technical solutions, not as a skill or, service, or magic dust.

Delivering software is hard, delivering it frequently should be easier, or at least make it easier over time.

Setting your process, project, and system for stable and frequent delivery is a complex and often puzzling endeavor.

Through this article, I want to give you guidelines to help you get to smooth delivery of your cloud-native software.

I will try to give you an insight into one full end-to-end development and delivery set up - a blueprint of a full SDLC production line, as I like to call it.

Prologue - stay confident, deliver frequently

In the majority of cases, the main measurement of anything we do in software development is business value.

For a long time in software delivery history, we have delivered “full products”, something that we learned from production in the other industries. We reasoned that the whole thing needs to be assembled, tested, and delivered exactly as pre-defined. This resulted in big value releases, the prod deployment events that were perceived as life-changing events every time it happens.

The problem with big releases is their big value. You got just one job to do and that delivers value, so delivering a big chunk of value is going to make your stakeholders happy at some time in the future (if the market does not change by the time we are done), and is going to make you and your stakeholders anxious about tons of things.

The pain is - a big chunk of business value in software means many changes, lots of new things, lots of software to test and to confirm. And if it goes in the wrong direction, as it most certainly will, one wrong change can take down the whole release.

This sounds like a hyperbolic story in modern times, but believe me that some of the biggest players in the industry, including SaaS giants, have some gigantic releases. Imagine quarterly (as in four times a year) releases on some important SaaS platform that causes billions of euros in damage from some undiscovered bug, only to roll back and cause more damage to companies integrating some other new features that came with the release which had to be rolled back. Amazing stuff.

source: xkcd

source: xkcd

So, the solution is to, as most of the readers will know already, set the pace of your SDLC to a lot shorter cycles. With this you will get:

- Shorter lead times to delivery of a single feature.

- Less value in single release, reducing the anxiety and increasing the confidence. You do not get too anxious about releasing one feature, and then maybe rolling it back quickly or it causing small financial damage.

- Easier to test.

- Easier to locate the problem.

- More frequent feedback loops.

- You exercise the whole CICD system more often so the system itself is more polished - iterations add finesse.

You will have to get rid of:

- Releasing fortnightly/monthly/quarterly/yearly… even worse.

- Long discussions about preparing everyone for moon landing, sorry, I meant production release.

- Long reviews, testing sessions, and security checks.

- Slow and outdated CICD system, lots of manual work (which is allowed if everything is slow).

This is a part of setting up your organization to work in a full DevOps model in some nice agile or lean process setup.

Important note: I am mostly focusing on the architecture and technical solutions, so talking about team, work management process methodologies, release cycles and other generally organizational decisions is out of the scope of this article. I will keep focusing on the technical capabilities you want to provide and connect in order to let your software delivery fly.

Path to Cloud-Native SDLC

Cloud-native principles are having a major influence on our thought process while creating our full SDLC supporting structure. This is how I like to present them in short form (good for conversation or whiteboarding).

Four central ideas of Cloud-Native:

- A service-based architecture.

- API-first.

- Containerization.

- DevOps.

Eight elements of Cloud-Native path:

- DevOps evolution.

- Modularity/reusability.

- Statelessness.

- Right tool for the right task.

- Self-service tooling and infra.

- Automate everything.

- Continuous delivery and advanced deployment methods

- Continuously optimize and improve your ecosystem.

I am bringing this in to reflect on what is driving us on the path we are taking towards fully optimized business value delivery. This means through the delivery process and good dev experience.

Service-based architecture - not microservices, not CQRS, not magic, just services working to deliver capabilities, some big, some small, some micro - all delivering business value and allowing us to have decently short and as much as possible separated release cycles for all.

So, where do we start? What is making our SDLC tick?

Flow of delivery - in theory

Every production line has its tempo, speed, and throughput (intentionally staying away from official theories and terminology):

- Tempo sets when and how often production or processing of separate element starts.

- Speed sets lead time from start to finished product.

- Throughput is the capacity for parallel production lines.

Setting the tempo - Source code management

Getting into the core of the topic - SCM (most usually git) has all the capabilities we are looking for in the module that manages the tempo of our SDLC. We can trigger events on:

- Branch created/pushed to repo

- Before branch is pushed (with a hook)

- PR created

- PR merged

- Merged to certain branch (master)

- Creation of certain branch (release/xx)

- Basically, any other event related to operations done with source code.

Need for speed - quality and compute

Throughout the development of your system, there are going to be many automation and series of automation (AKA pipelines) that get triggered on different SDLC events. They are mostly:

- Builds

- Deployments

- Quality gates

- Scans

Most of these are essential for the quality and delivery of your software, they will be there every time you so much as touch the code, not to mention deploy it. Their level of presence makes them a major influence on lead times within the delivery cycle. Keeping automation execution times low is essential for efficient software development and delivery.

Capacity and throughput - 500 drills theory

source: xkcd

source: xkcd

Looking at the path to cloud-native, few items directly impact how we look at the throughput of our delivery system:

- modularity/reusability

- Self-service tooling and infra.

- Automate everything.

- Continuous delivery and advanced deployment methods

In the secondary manner, statelessness and the right tool for the right task as part of solution space, are also bringing some solutions into the space.

I like to set it up in this way: Creating building blocks for self-service tooling, automation, and infrastructure for every team to build their own continuous delivery and custom deployment methods.

Of course, self-service means that there is a team around with almost a sole purpose to hand-hold everyone through the process of self-servicing, assembling, and configuring stuff.

In simple terms - we want it built with capabilities and at the level of flexibility that allows us to spawn many on-demand pipelines and development environments.

Measure and optimize

Every part of the CICD system has to be well monitored and analyzed. Measurements around the system should be used for determining the fitness of the technology solutions and identifying the next improvement area.

Delivery flow in practice

So, beyond the fancy theory (and all the comedy), the technical embodiment of SDLC starts with the quick delivery review and breakdown of needs.

So, let’s set the stage:

- Code is in git, using the “GitHub-flow” model, basically branches for features that merge to the main branch where they are considered prod ready

- Is deployed to Kubernetes

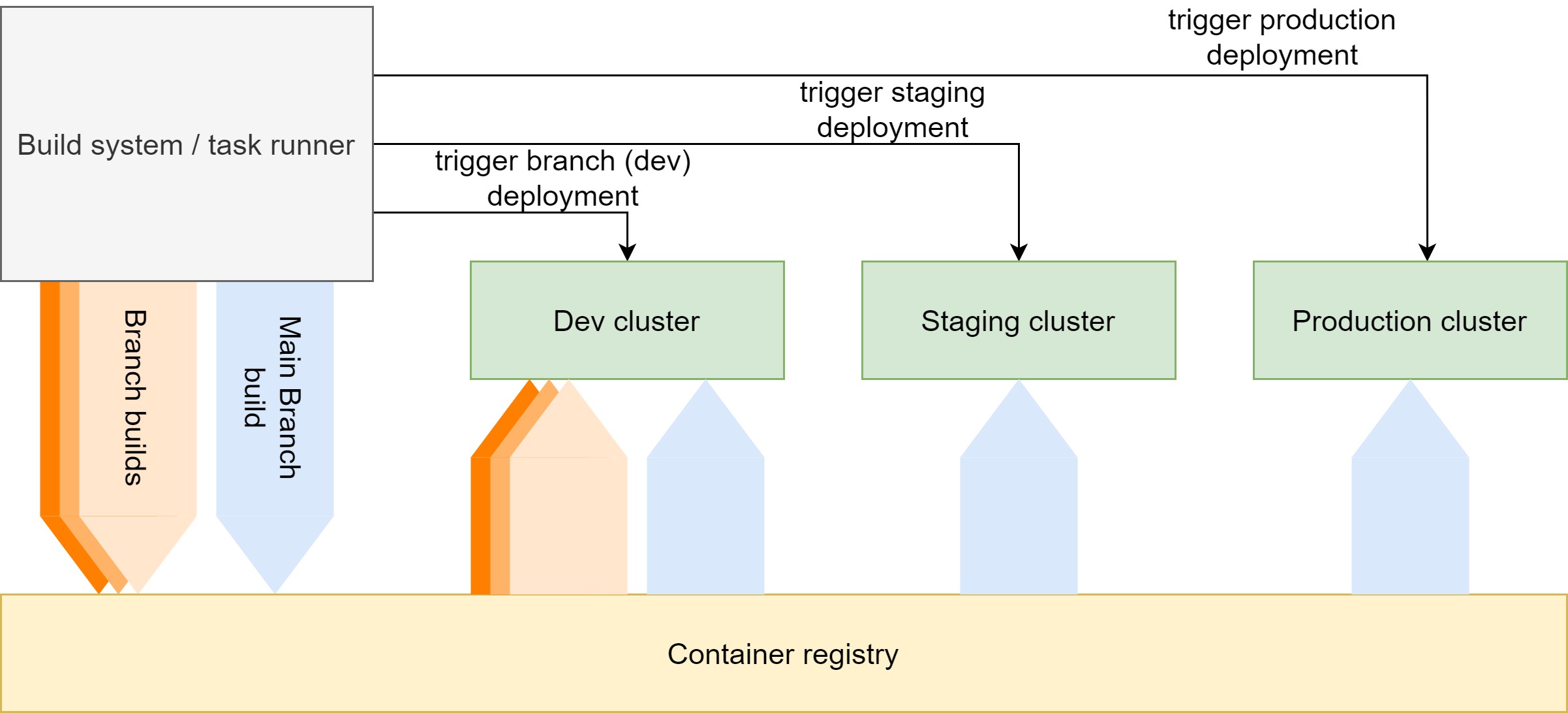

- Needs 3 types of environments - dev, staging/preview (pre-prod) and production

- SCM flow is setting the expectation that every feature branch has a separate environment

- Has dependencies deployed to the cloud

- We want to always be able to release

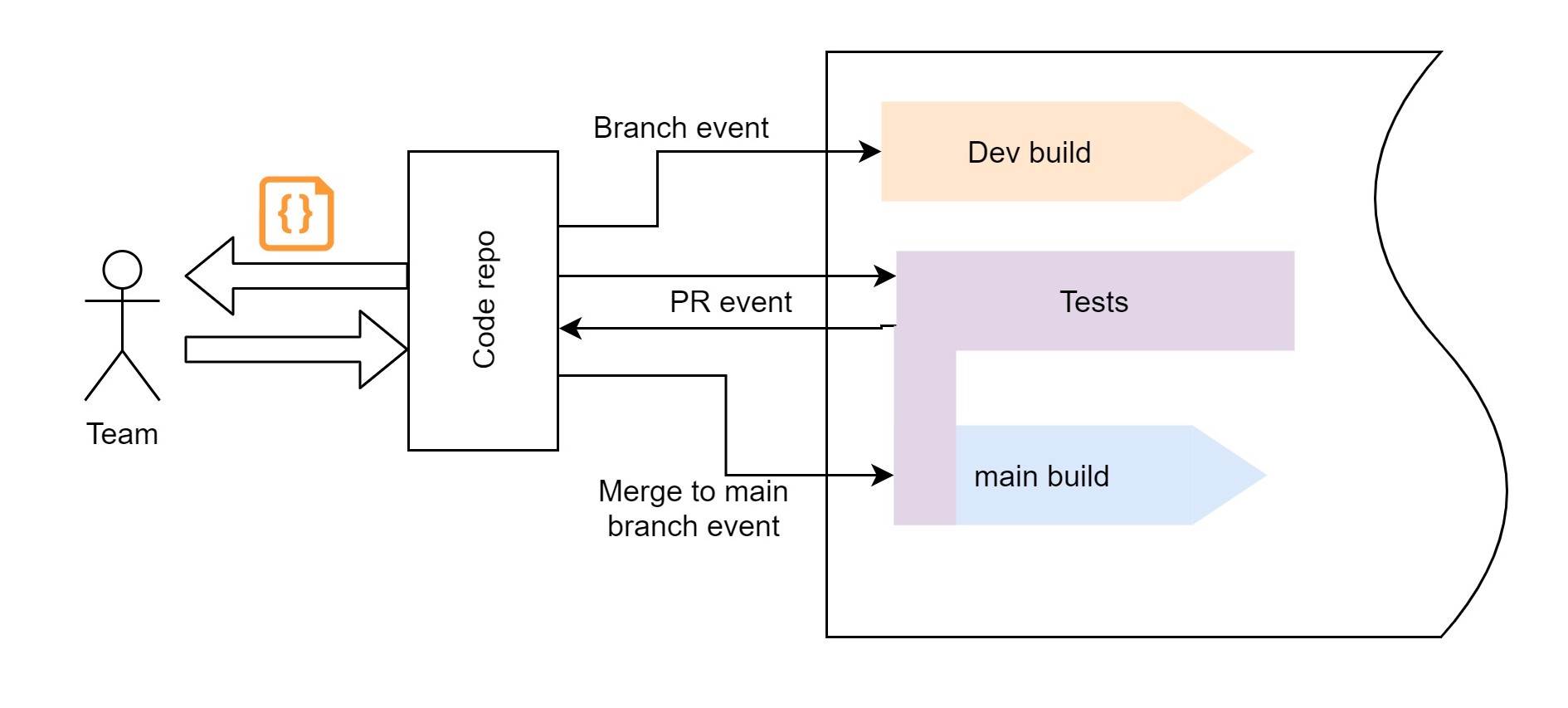

Source code flow - code comes in

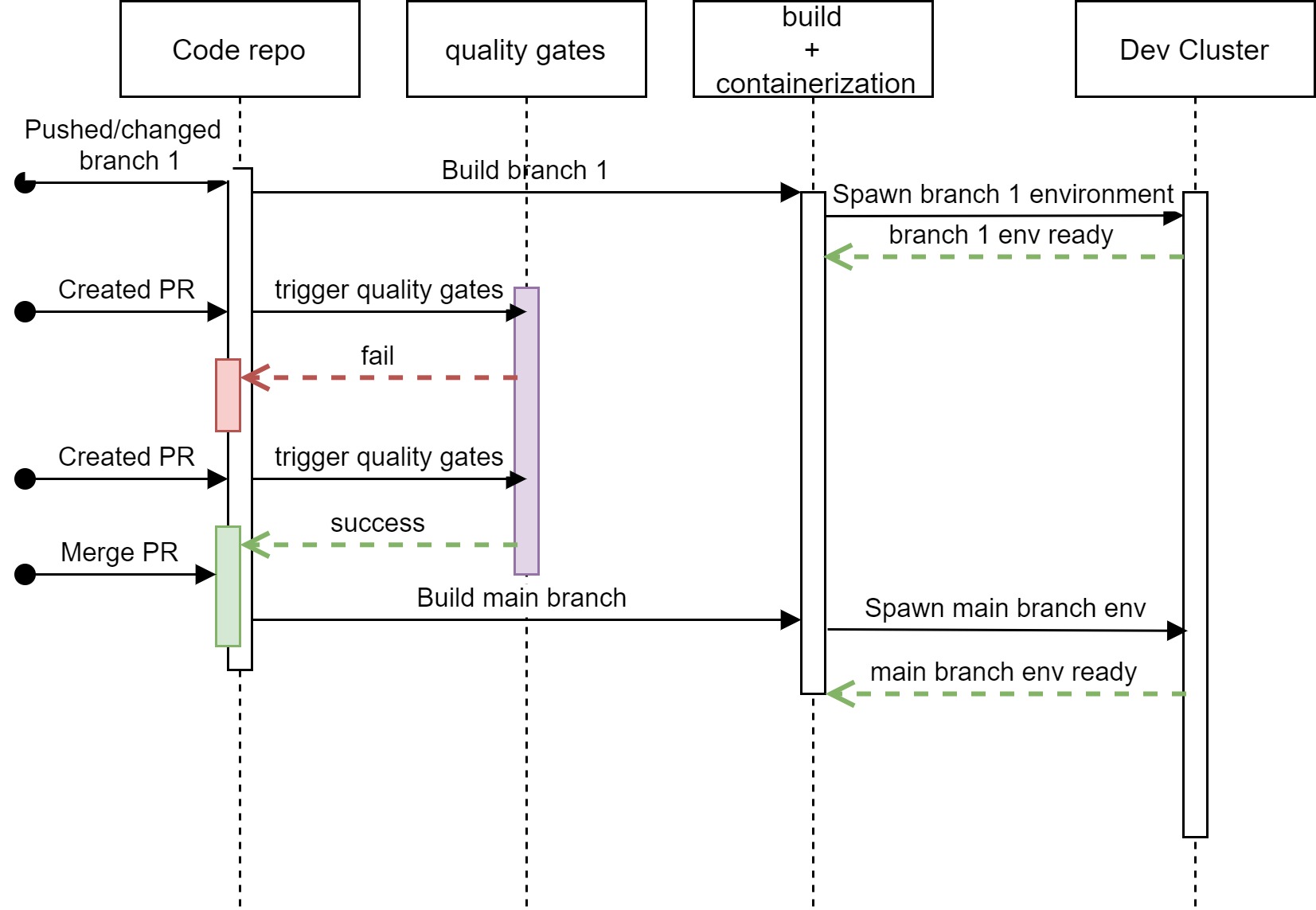

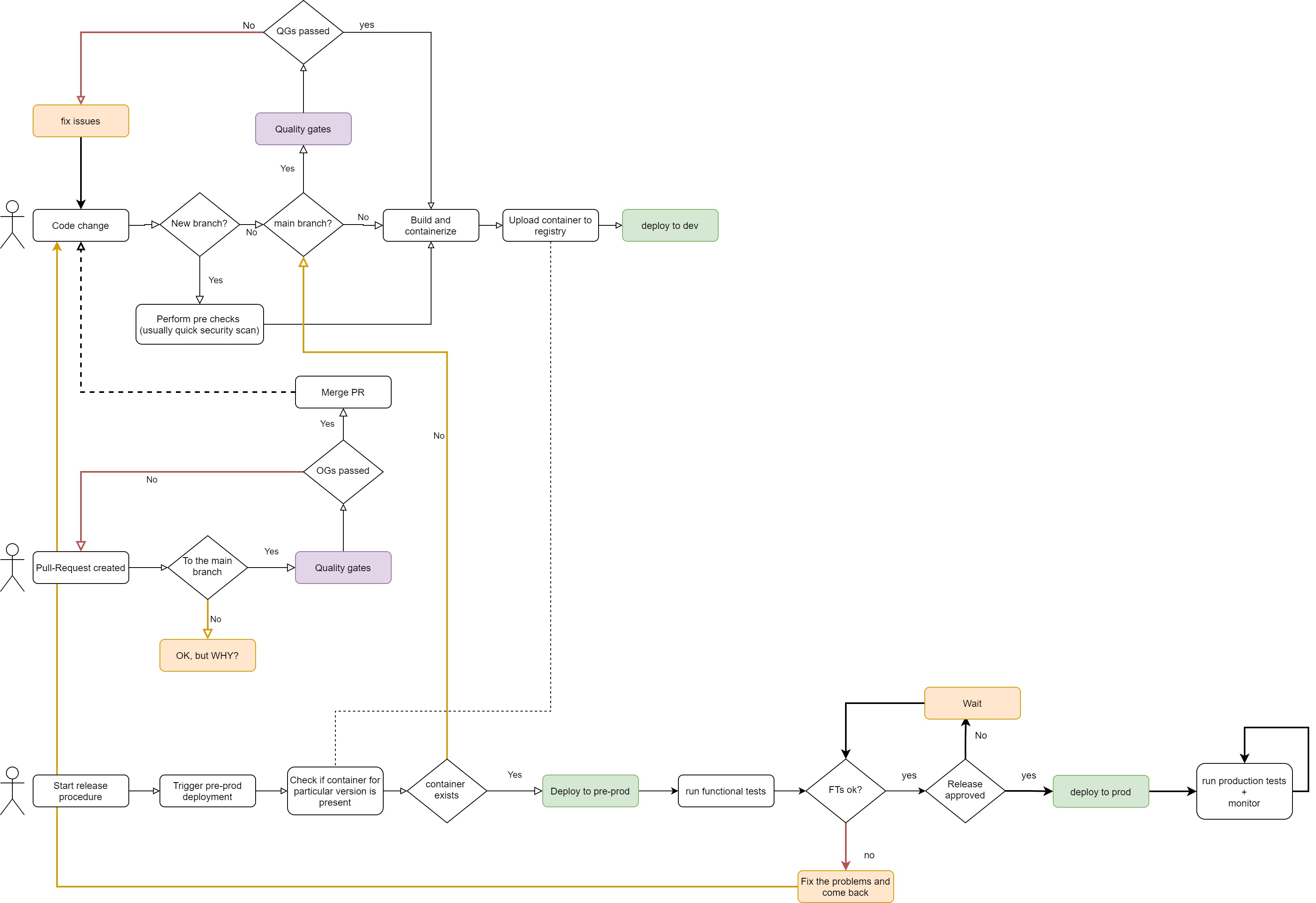

As already described, we want SCM to be the main driver behind our CICD setting - setting the rhythm.

We would utilize the hooks from whatever source code repository we are using to trigger certain actions in the system.

This means that development flow until actual merge to the main branch will fully be driven by the events on the source control:

- New branches created and pushed

- Pull requests created

- Pull requests merged

The containerization

Containerization implies another repository/registry system - the one to keep all the containers we will be building in. Ideally one with some additional features like security and integrity scans and maybe some other fancy stuff.

Apart from what is in the container - you might need more than just a place for your app code to live, there are of course different data persistence layer components, networking, storage, etc… If these are all in the cloud for you, please make sure you got as much as possible infrastructure as a code (ideally have EVERYTHING AS A CODE POLICY in the dev team). Avoiding any manual change is always the best, it also makes it optimal for automation.

The development environment - no judgment place to work

When it comes to the early phases of SDLC, you want it free-flowing. There is no point in scrutinizing any aspect of work in the starting phase, not just of the system, but of any feature. If every feature is a built-in separate code branch, that is.

To make sure this is followed, also make sure to block any pushes to the main branch (whatever you call it).

So, we basically want every new branch created on the repo to spawn its own environment in K8s, no questions asked.

On the other hand, you will probably never need separate databases and other supporting structures between different dev environments - it is good to keep things simple on this side.

For this you need:

- Build pipeline ( no quality gates used apart from the one that is actually if the build succeeded or not)

- Build pipeline will output the containerized application, so you need to structure your usage of a container registry

- Deployment enabling a multitude of environments.

Multitude - Imagine 3 people on the project, each having some features they work on and some test/PoC, totaling 3 branches per person - you would ultimately have at least 9 builds, and if they are successful, 9 separate environments under one ingress in your dev Kubernetes cluster. Depending on your application’s API structure this might be a source of complexities as well.

Mainline - the pull request (PR)

Getting the code further through the delivery process should depend the most on what happens next in the source code story.

After the successful development of a new feature, it is time to merge it to the main branch and start preparations for production release.

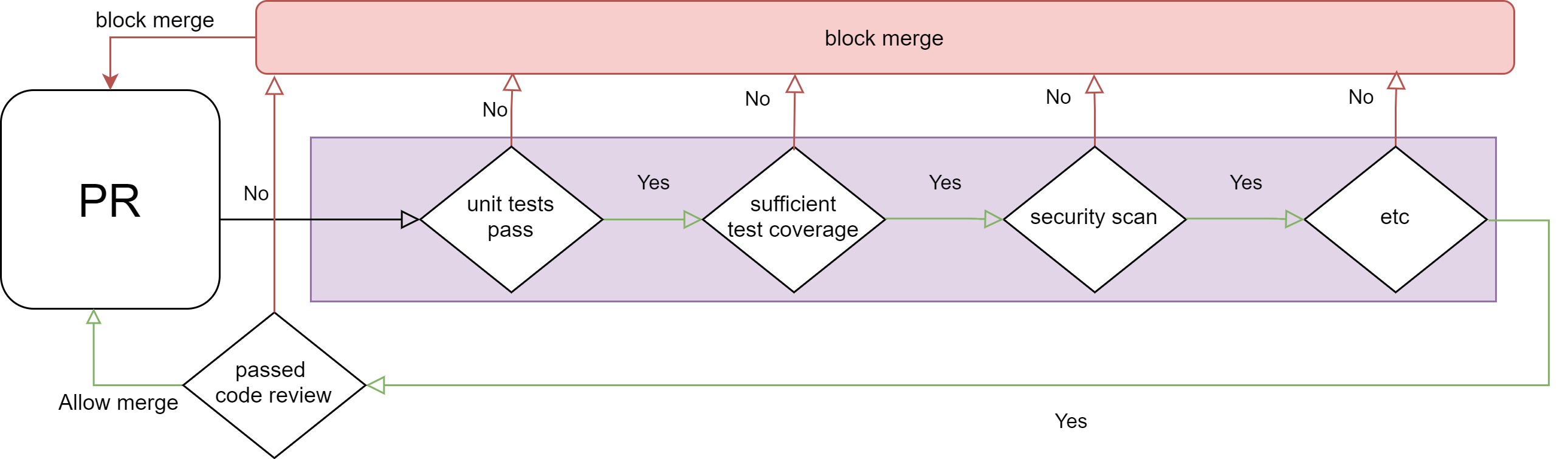

This is where pull request is created and code should go through all imaginable checks before ultimately being merged and built one last time.

So, when PR is created, the CICD system starts a sequence of operations, mostly related to code functional and non-functional quality, and tests - ofc we are writing tests.

These are known as the quality gates.

> The Quality Gates are all outputting go/no-go status and it is used fr both the PR merge and the final build of the code version.

Without all green, the very button to merge the PR or any pipeline to merge the code should stay locked.

Not complete, but hopefully illustrative list of quality gates:

- Unit tests

- Integration tests

- Static security scan

- Code quality scan

- Peer review

Merged! Now what?

The Last Container!

Not exactly, but the moment we have merged code to the main branch is the moment this code is in the release candidate state. It is at this moment that we build this code version for the last time. From now on we would just move built and containerized code around, no more fiddling with the code.

You should be able to always consider the code merged to the main branch production-ready, if not, this is the first thing you should fix

Release the Kraken!!!

Now, in building your CICD architecture comes the time to deliver the app version to the new environment.

The next environment can be production or staging, which also determines what you are doing on the main branch dev build. If you have no need of a particular staging environment, you can also run final quality gates (functional, acceptance, API contracts…) on the dev environment of the main branch build.

In some situations, you can have even more separated environments - I worked on software that needed special security checks and compliance review environments to continuously run production code and certain replication of prod data…

In conclusion - beyond deploying the main branch build to the dev environment, you are only promoting it further. it is about performing the same action on the same, already built, container, but on the different environment and running post-deployment tests. The only difference might be the environment variables on deployed container that you use to control the configuration.

If you are maintaining any kind of consumer-facing application (API or UI used by internal or external consumers), you will mostly have a staging (pre-production) environment for a few purposes like:

- Testing the app prior to going to prod

- Testing content prior to going to prod

- Having next version available for clients’ integration purpose

After all the tests are done, you are ready to open the gates.

Promote - actual terminology for the release in this cloud-native approach is quite often “promote to staging” and “promote to production”, for the reason that you are taking the container built from the main source control branch and deploying it to dev (as a branch-build), then taking the same container and deploying it to staging and then to prod, which is basically promoting it to the next level.

So, this is it, go back to the part where it says “code comes in” and start again.

Here is the holistic view of what you’ve just read about:

Comments